When children come to my clinic with the question – how can I learn to read? I explain to them that everyone learns very differently, and there is no one method that is correct for everyone. Each child reads differently and learns differently, and therefore each reading problem will lead to different methods and ideas.

When Eli came to his first lesson with me, he didn’t ask – how can I learn to read. Instead, he started telling me that he could not read. When he left at the end of our one-hour session, he looked like he had eaten the most delicious ice cream; he was dancing while talking to the teacher who came with him; “Did you hear? I read. Did you see it? I can read. Bella made me read. She is a magician!”

He could not read

Eli is 10. He came to his first lesson with his teacher. Usually, the adults who accompany pupils are the parents and not the teachers. I was impressed by the strong connection between them. The teacher was also the one who contacted me by phone a few days earlier and said that she had heard about me, and after they had tried everything in school to help but weren’t succeeding, she felt she needed advice from an outside source.

The teacher told me by phone that Eli is intelligent and highly motivated but feels frustrated and an idiot because he could not read. At times he almost breaks the walls down. He is on Ritalin to help calm him down. He comes from a low-income earning family, and parents in the school had donated money to help pay for private tutoring.

It was impossible to say no, and I was curious to meet this child who touched the hearts of the entire school, and they had collected the money to help him.

Ritalin is being given too quickly

I had requested that he would come without Ritalin. I think Ritalin is being given too quickly to children to solve their reading and math problems without attention as to its impact. Ritalin doesn’t help the child explore their own unique way of learning. I believe it mainly helps the teacher to be able to handle the behavioral problem in a class of 30 and more pupils. When a child comes to our lessons with the question- how can I learn to read, and they have taken Ritalin the same day, I can see the drug’s effect, rather than the child, as is.

It was impressive that after 23 years of special education experience the teacher had come together with him.

I wondered what the problem could be that nobody had seemed to manage to find a solution after all these years. None of us would have believed that already after one lesson, the difference would be so dramatic.

When they had just arrived, Eli ran up the stairs without hesitation and, almost without breathing, started talking; “How can I learn to read? I need to know how to read like all the other children. Can you help me?” He was hyper, and I didn’t know if it was from excitement, fear, or not taking medication. It didn’t matter to me. He continued to talk rapidly. “I cannot write properly…I cannot read… My maths is not so good.” The minute that I could get a word in, I quietly said, “this room doesn’t want to listen or hear the word can’t. We only accept or even listen to words like ‘I want to improve or try. The best sentence that this room wants to hear is “I will try and will succeed.”

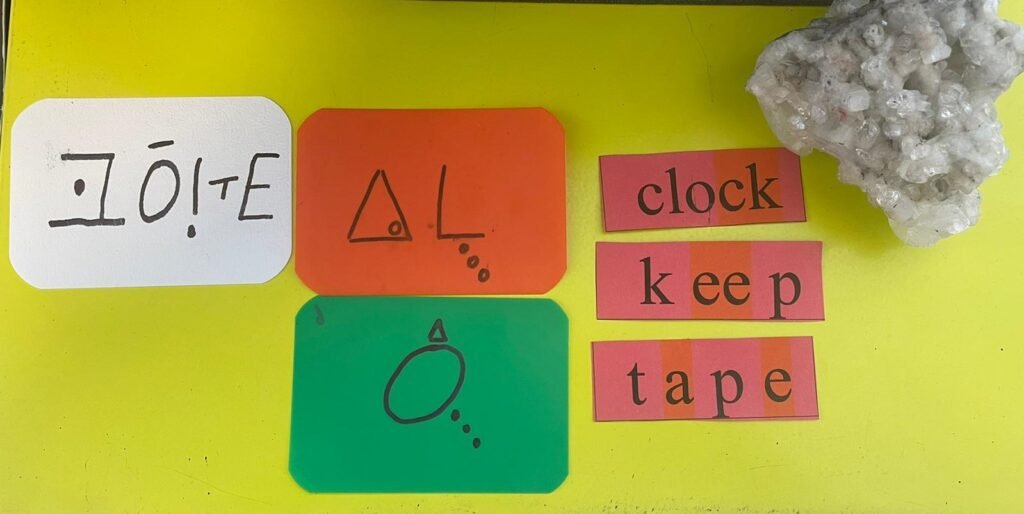

To put the signs together

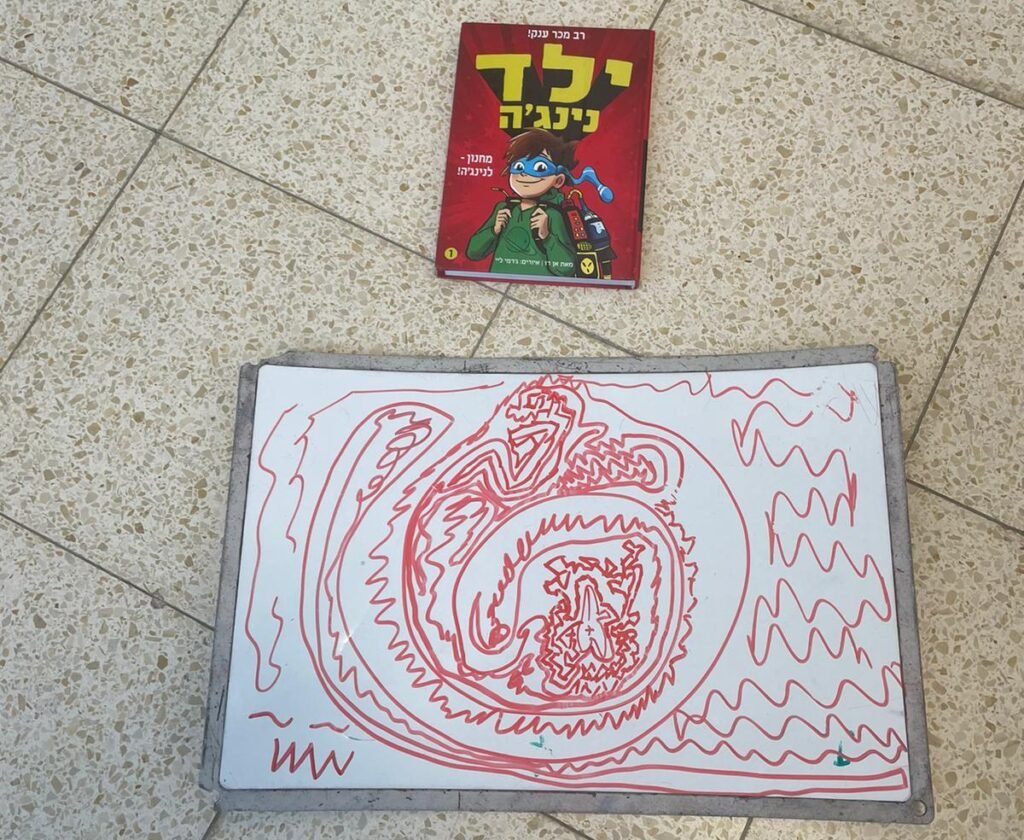

Eli was right-brained dominant, which means that it was easier for him to see the whole picture or word. In Hebrew, the words have vowels under the letters. Lots of details for a right-brained person to deal with. Firstly, we did physical exercises to calm him down and get his brain working, and then I showed him flashcards with shapes and asked him to look and remember and draw on the board. It was fun for him, and already he was feeling a feeling of success that he could do it. He was sitting quietly and calmly on the chair—no sign of attention problems. I explained to him how to look at a word and put all the signs together. Obviously, when his mind was both active and calm, he managed to organize all the information and use what he has absorbed in the few years he sat in class. I then gave him a page with a short story, I told him the name of the story, and we discussed what it could be about. I wanted him to feel comfortable as much as possible before he read. He then took the page and started reading. Every few words, he looked at me and asked: “Did I really read correctly?”

“Of course,” I said quietly, containing my tears so as not to flow into a river. Eli’s teacher, sitting in the corner, looked at me aghast, shivering in amazement: “No-one will believe this. How did you do it? It was magical!”

Can the system change?

I felt lucky to have been able to connect the parts of all those years that he had been taught and help him to start reading. I felt lucky to have the beginning of the answer to the question: how can I learn to read. I felt lucky to have been part of a miracle of a child who couldn’t read when entering my clinic and leaving as a student that could. We will have to follow up the lesson, continue with the teaching, and get him up to his class standard, but the sentence “I cannot read” would not describe him anymore. He could now ask himself – how can I read better. His understanding and recall were perfect.

Besides feeling lucky, I also felt frustrated. How can it be that after five years of schooling and special education teaching, he was still not reading and that nothing had sunk into his brain? There are methods in the system, but the method doesn’t work for all. Eli had been taught reading as parts – meaning letters and vowels and not whole words. Instead of changing the method, the system wants to change the way a child naturally thinks. How many hours of frustration it would have saved if only the system had found joy and invested in the art of teaching and not only in the method. A pupil is not a method! One must be creative to change a method into the individual need of the pupil. We had achieved in one hour what was almost “wasted” teaching of so many lessons for so many years.