This topic comes up again and again. After one session, a parent will ask, “maybe I should do a reading assessment for my child?”

Many pupils have difficulty at school with reading subject matter, understanding text, and also no real interest in books, which stems from not really collecting the information efficiently. Most children with reading problems prefer comics as they can guess what is happening and do not have to read and remember every detail. Teachers would recommend doing an assessment when they see this frustration with reading.

Are reading assessments really effective, and do they explain the hardship and give answers on how to deal with the reading problem? Or is the whole thing brushed off with the concept “Dyslexia”? The school advisor recommends reading assessment, and of course, the internet is full of advice about it as well.

Limitations of assessments

Being a teacher of children with learning challenges for over 30 years has given me a different perspective on the benefits of reading assessments and has shown me the limitation of those assessments. I have asked myself again and again; are these reading assessments truly effective? I see parents, teachers, and children using the titles they have been given, such as dyslexia, in ways that are often not beneficial in dealing with the problem but rather giving legitimation that they have a difficulty, so let’s not really deal with it and find ways to get around the hardship.

Merav’s mother called to ask if she should send her daughter for a reading assessment. She had been coming to me for a few weeks at the time, and I curiously asked for the motivation of the reading assessment. We knew how intelligent Merav was, and it was clear that she had not yet reached her potential of getting the full benefit from reading material. Her mother explained to me that it was important for her to receive higher marks in her matriculation examinations so it would open studying opportunities for her in the future. She knew that if Merav would be assessed, she would get some special facilitation from school, such as more time.

Before answering, I wanted to talk to Merav. I knew already, after having worked with her, that she didn’t want to take on the responsibility of making an effort when it came to reading texts or answering questions. I knew that even when she could read a text, she would often respond with, “I don’t know, you tell me!”. During our lessons, she often asked, “so what should I write as an answer?” and I would answer: “what do you think is the answer?” I would encourage her to think about the different options we have as an answer, and usually, she then knew what to write.

I had the feeling, that as soon as she would get her reading assessment, it would be much easier for her to rely on someone else’s opinion and not make an effort for herself and instead would use the assessment as an excuse “but I am dyslexic or dysgraphic.”

An assessed dyslexic story

It reminded me of the story of Gad. He has just contacted me a few days before the phone call from Merav’s mother. Gad came to me just before going to university. We had worked together when he was in junior school, and he was then assessed as dyslexic. He now came back as a grownup and wanted to know how to study without his ability to read fluently. “But why can’t you read?” I asked. “Because I had three reading assessments, and they all told me that I was dyslexic and wouldn’t be able to read fluently,” he answered.

I told him that the word dyslexic doesn’t mean anything to me, and I suggested that we focus on how to overcome and deal with his reading difficulties rather than focus on them. We learned where the problem lies, and he managed to read, read and understand. The skills he would need for his university studies. It is not that the assessments were not correct, it was that they didn’t help him find a solution. They focused on the problem rather than on ways to solve it.

The secrets of body language

One can tell a lot by just taking note of body language. The way a child walks, talks, and dresses. It can be with what a child wears or the way they fix their hair. It can even show in things like how they organize their pencil box. When a pupil walks in, dressed to make an impression, it means that they care about the way they feel and what others think of them. When looking at how their pencil box is organized, one can see their care for details and organization.

Sometimes, body language is more effective than the reading assessments that are handed to me (and which I never read), as it reveals so much. When Merav walked in, she gave me the feeling of not wanting to try for herself. She sort of slinked in and sat down with a face of failure before even starting. She did not organize her hair, and she wore clothes that were bigger than her body as if to say, “I don’t want you to really see the true me. So much to learn from simple things.

Sharing thoughts with pupils

In our lesson this week, I told her that her mother had asked me about sending her for a reading assessment. I asked her why she wanted to do it. Suppose you went for an evaluation; what sort of things would you imagine it will help you with? She said she wants to get “less writing” in school and perhaps someone to read to her because at the end of the text she doesn’t understand what it is all about.

Would you want someone to write and read for you? I asked. Do you want to do your tests orally? Do you want to go out of the classroom and get help? She was a bit puzzled at these questions. It made her think perhaps, that she would be taken out of the general classroom and made into a “special case.”

“Why shouldn’t we first try and improve the things that you find you are struggling with?” I asked. “Why don’t we try and strengthen your weaknesses? Why don’t we deal with the problem instead of getting a certificate that you have a problem? Are reading assessments effective? Do they solve the issue? Do they help pupil strengthen their willingness to overcome? Do they motivate pupils to find a way and make a bigger effort for themselves?

How to start

When a pupil gets to matric, and I find that given more time would help achieve a higher mark, I am all for the assessments, but before we get to that stage, I prefer the child to learn to make an effort. True, it is much easier to ask someone else to do and to assist, but sometimes we must find our own way to get to the answers.

Merav sat down and said, “I need help in chemistry! I didn’t understand anything in the lesson today.” She took out her notes and sprawled herself on the table without any feeling of ‘I am going to tackle this one and overcome.’

“So, what must I write?”

“Firstly, let’s sit up straight and take some deep breaths, making our spine stretch and allowing oxygen into our brain,” I suggested, “and then we will start. “

How do we learn

“I don’t understand the question,” she said.

“That’s okay. I am not a chemistry teacher and am not sure that I ever learned this, so I don’t understand it either. Let’s look at the subject matter together and try and understand that first, and then the questions will be easier to fathom out..

“What does the word element mean? “She asked.

I knew that she expected me to answer her. Usually, she gets answers for her homework from her parents or teachers, who tell her what to write. I knew that I needed her to take responsibility for dealing with things on her own. I was actually happy that I didn’t know much about chemistry.

“Why don’t you google it and then explain to me what an element is?”

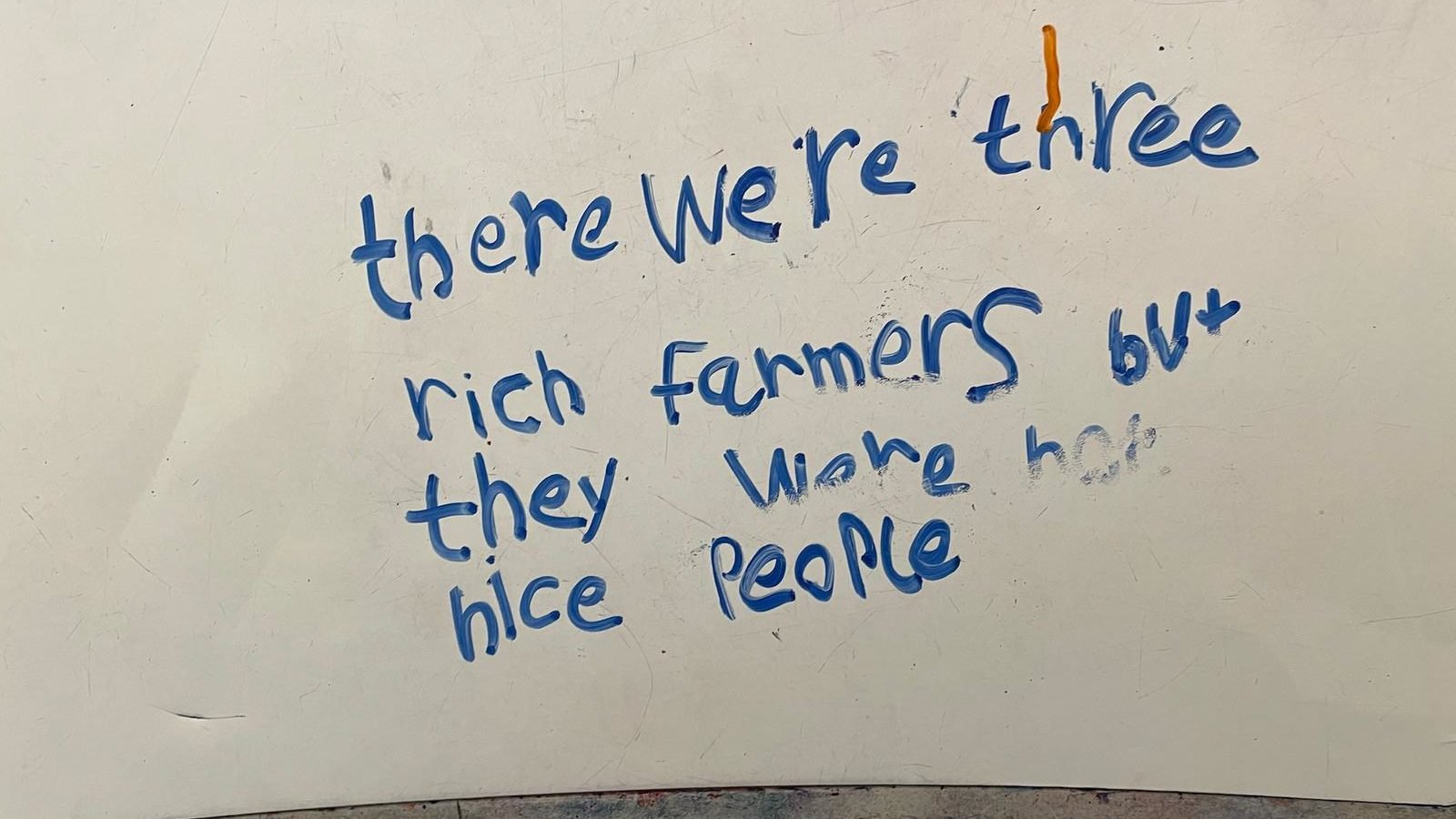

She explained what she had discovered, and then we went to the information she had in her book and discussed each sentence. She marked the different elements with different colors and suddenly understood it all and could answer the questions. Slowly her breathing became deeper, and she automatically sat up straighter in her chair. This was also a point that we could talk about reading pace. When reading slowly, it is much easier for a lot of people to gather all the details. If she had read this text quickly, there was no way there would have been understanding.

Summarizing the learning procedure for herself

We then discussed how things became interesting when she did something for herself and how she could cope with new information. I shared what I saw happening in her body with her, and she shared the feeling of achievement and pride, doing for herself.

For me, teaching a pupil to read is giving them tools for life. It is not only about reading but about facing a challenge. Do reading assessments give us tools for life skills? Do they provide tools for children to deal with the many challenges on their way? Sometimes they do, but they are often being done too early, and then they just help the pupil avoid their difficulties, and thus they miss out on the wonderful feeling of overcoming a problem and a feeling of “I did it!”

The process of learning

A big part of the process of teaching a child to read has to do with what stops them from reading. You can claim that this is what reading assessments aim to do, but the outcome is very different. The process of teaching Merav showed her how to make an effort and convince herself that she could do much more than what she believed she was capable of. What was the actual problem with her reading? She just read too fast, and there was no way that her brain could analyze all the bits and pieces of information and achieve an understanding of the material. She read without giving herself time to think about what it was all about. So, in fact, she had to learn to read slower and also how to collect information on the way.

The process of learning is about facing difficulties and finding a way to overcome them, just as in life.

When a pupil finds their unique way of learning, it helps them overall in other fields of their life. Merav’s body posture has changed; she started to take care of her appearance, felt more confident in her class, and enjoyed exploring for answers on her own instead of asking what she should write. We’ve never discussed the option of going to a reading assessment again as she didn’t think she needed it anymore.